In Focus: Remembering Julius Shulman, 1910-2009

I would be kidding myself to say that I wasn’t a nervous wreck as we drove along Mulholland that Saturday afternoon. My new acquaintance Michael Locke was buzzing with advice on how I should conduct myself with Julius.

His tone was casual and carefree, intentionally disarming, and he would smile to himself as he recalled each bit of worthwhile advice. “Never inquire about when he shot a particular photograph,” he would say, “or ask what it was like to shoot a subject. Julius will invariably respond that he photographs his subjects. ‘Do you see a gun in my hand?’ he will ask, with his index finger pointed in the air like a loaded pistol!” I was told to never use the word “interesting” as a compliment. According to Julius this word is the worst in the English language. There are so many better ones with which to express oneself.

Some photographers are synonymous with the cities they have immortalized. Through his perfectly orchestrated and technically executed photographs, Julius Shulman was able to capture the architecture, culture and idyllic lifestyle of Los Angeles in a way that for many was impossible to resist. As Christopher Hawthorne, architectural critic for the Los Angeles Times wrote, “To look for any length of time at a Shulman picture of a great modern home in L.A. is to get a little drunk on the idea of paradise as an Edenic combination of spare architecture and lush landscape.” Shulman’s luminous photographs of homes and buildings in Los Angeles and across the country would bring fame to a number of mid 20th Century architects and make him a household name in the architectural world. Between 1936 and 1986, Julius Shulman completed some 6,000 photographic assignments in North America and around the world. Throughout his 72-year career as a professional photographer, he has documented nearly 8,000 subjects. Every single building recorded in black and white photographs and 35-mm color slides.

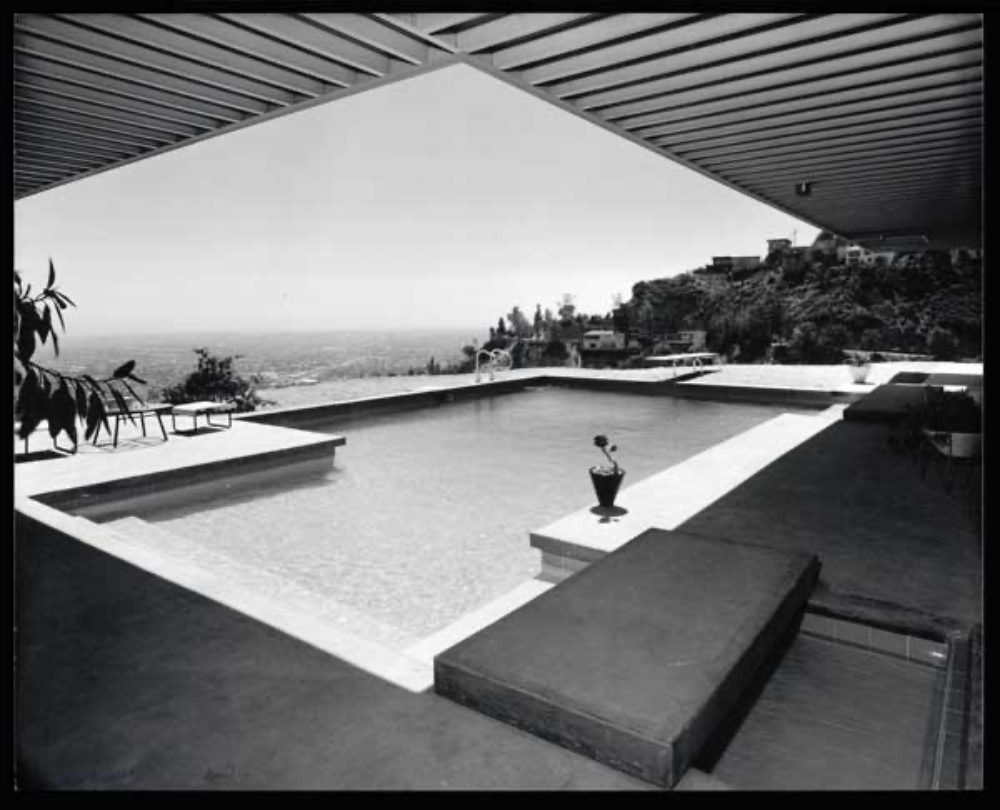

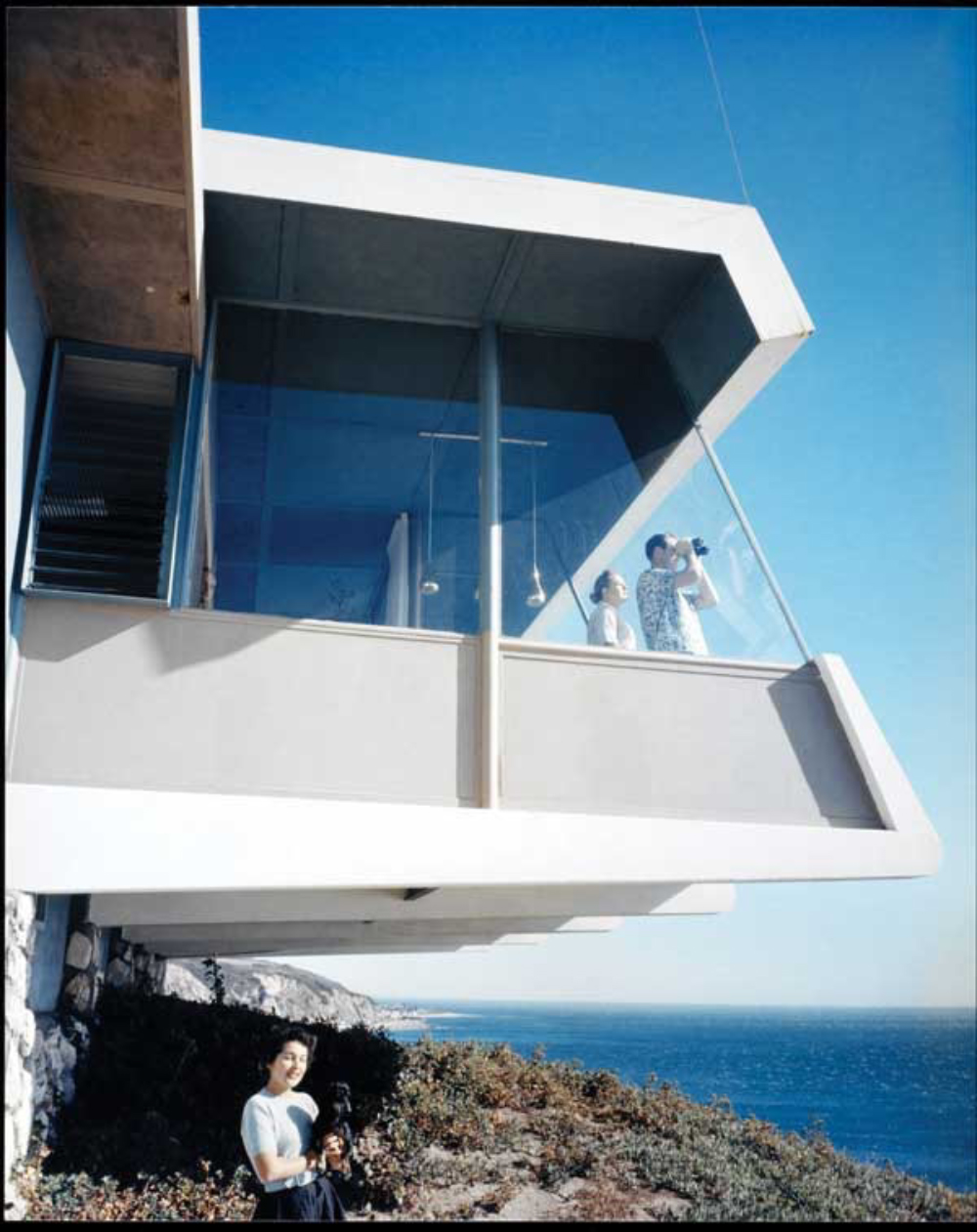

Beginning with Richard Neutra in 1936, Shulman’s list of clients included many of the most well known architects of the time: Rudolf Schindler, Frank Lloyd Wright, Gregory Ain, Charles Eames, Raphael Soriano, John Lautner, Eero Saarinen, Albert Frey, Pierre Koenig, Harwell Harris and many others — all pioneers of contemporary architecture. If a book was being published which featured modernist architects, Shulman’s work would most likely be included. After the Great Depression, magazines including John Entenza’s Arts & Architecture, Architectural Forum and others turned to Shulman to document the exciting new architecture of the time. Shulman provided images of beautiful people in beautiful homes. His 1960 black and white photograph of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 22, a glass and steel home built for Carlotta and Buck Stahl in the Hollywood Hills, secured his reputation. The photograph, taken from outside the cantilevered house, depicts two women dressed for a night out, but at the moment are sitting quietly in the living room chatting. The strong horizontal pattern of the structural framing overhead extends outside the house and mimics the grid of the sparkling city lights below. It was, as architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in the New York Times, “one of those singular images that sum up an entire city at a moment in time.” The photograph, perfectly framed and executed, is a “snapshot of the good life”, and has become one of the most famous architectural pictures ever taken in the United States. The iconic image is indicative of the way in which Shulman sold his vision of modernism to the world.

Julius Shulman was born on October 10, 1910, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants. At a very young age, the family moved to a farm in Connecticut, where Shulman first developed a love of nature and, in his words, was awakened to the effects of light and shadow. At the age of ten, Shulman arrived with his parents in Los Angeles. They set up a dry-goods store in Boyle Heights, which Shulman’s mother would continue to operate after his father’s death from tuberculosis in 1923. After graduating from Roosevelt High School, Shulman spent seven years auditing a variety of courses including geology and philosophy at UCLA and UC Berkeley. He returned to Los Angeles without a degree and was uncertain about his future.

Shulman received a KODAK Vest Pocket camera for his 23rd birthday. He carried it with him everywhere, photographing buildings, bridges and dams. He was captivated by the shapes and forms of the city. At the time, Shulman was earning money to pay the rent from the pictures he made. One photograph of the 6th Street Bridge over the Los Angeles River had won first prize in a national magazine competition.

It was a chance meeting with the architect Richard Neutra in March 1936 that would present Shulman the opportunity of becoming a professional architectural photographer. After a brief introduction from his sister to a young draftsman working for Neutra, Shulman was invited to visit one of the architect’s projects. The Kun House was located in Laurel Canyon, and Shulman, anticipating an opportunity to take some pictures, brought along his camera and equipment.

Not yet completed, the four-story house with its glass walls and dramatic setting inspired Shulman. “I had never seen a modern house before,” he later said. It “intrigued me with its strange forms that carved into the hillside.” Shulman took six black and white photographs, which he later developed into eight by tens and gave them to the draftsman, who shared them with Neutra. The architect, known to be a perfectionist, complimented Shulman on his composition and the way his photographs showed how the building was set into the landscape. With Neutra’s invitation to document other projects, Shulman suddenly found himself to be a professional architecture photographer. In 1994, Shulman told The Times that he was, “lucky to be doing the right thing in the right place at the right time…”

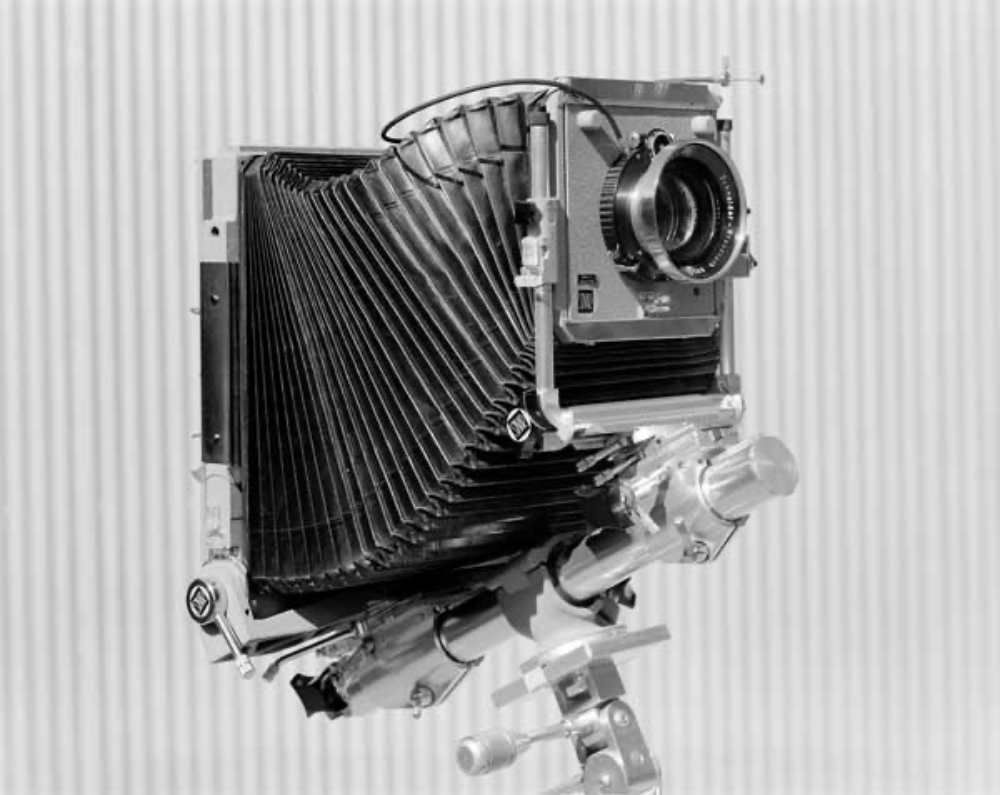

Through Neutra, Shulman was introduced to other prominent architects, including Rudolph Schindler and Raphael Soriano, from whom he would learn, and later refine, his craft. Schindler taught Shulman about lighting when he asked, “why on your interiors is the lighting equal in intensity on adjacent walls?” Shulman recalled, “What a lesson! In my use of floodlights it had not occurred to me that the illumination need not be uniform.” Shulman quickly developed his natural ability to calibrate light. Eventually, he stopped using a light meter and relied only on his innate senses. Later in his career, he would infer, “If you can’t interpret light and the way in which it plays with and defines its subjects, if you can’t understand the subtle and not-so-subtle rhythms of the sun, if you can’t recognize an architect’s intent the minute you walk into a room, no amount of money you can spend on a camera will make you a photographer.”

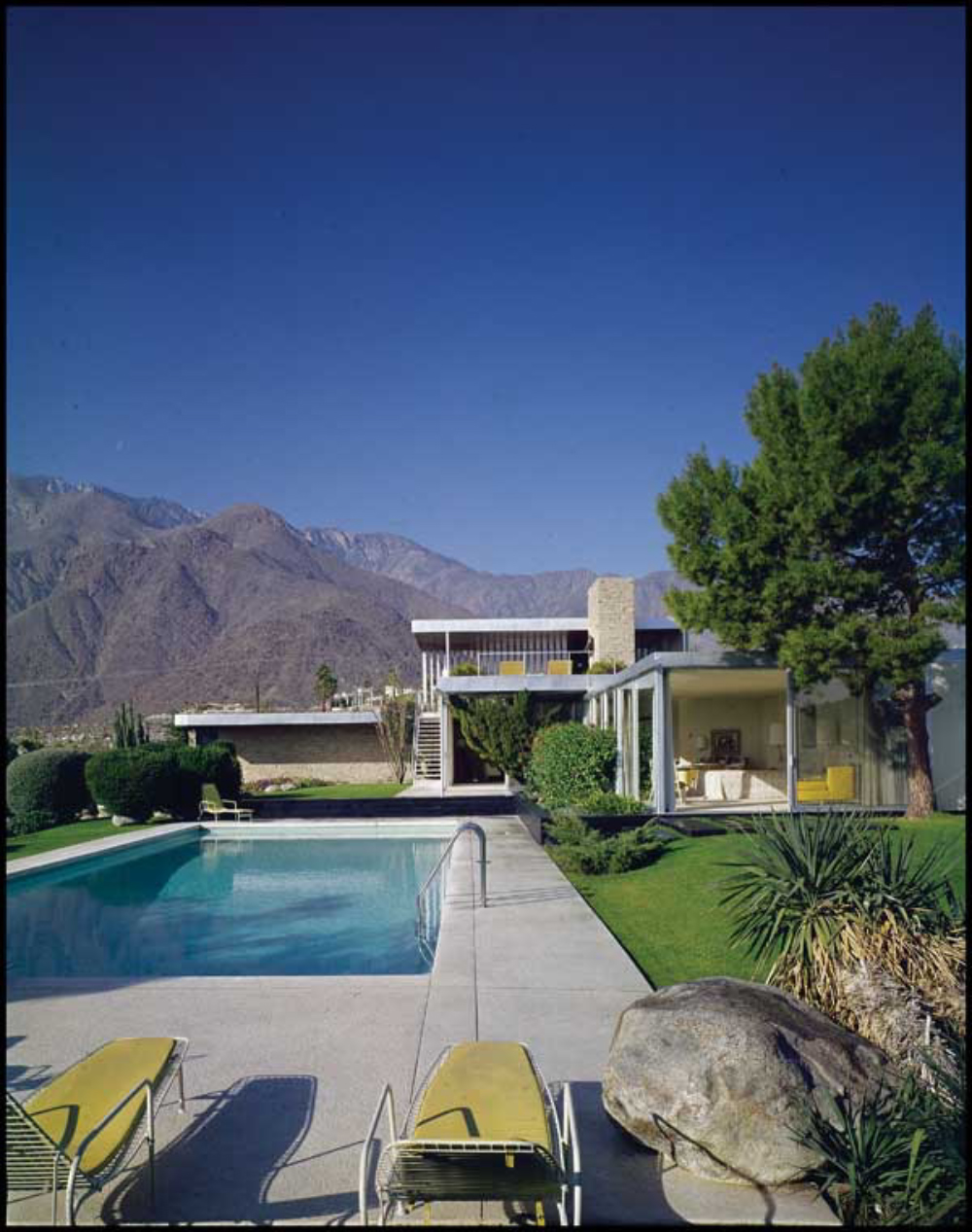

Ten years after the Pittsburgh department store owner Edgar Kaufmann commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to build Fallingwater in the woods of Pennsylvania, Kaufmann approached Richard Neutra to design his west coast retreat in the desert of Palm Springs. The 3,800-square-foot home the architect designed featured walls of glass and stacked stone that looked out toward the San Jacinto Mountains. Seeking the same attention Wright had received for Fallingwater, Neutra commissioned Shulman to photograph the home.

It was well known that no other architect for whom Shulman photographed was as meticulous and controlling as Neutra. Like clockwork, he would demand to look through the camera’s viewfinder, often making changes to the frame or adjustments to the exposure. Shulman would wait patiently until he was finished and then return the camera to the original settings once the architect turned his back. Their battle of egos was never more apparent than on the evening when Shulman photographed the Kaufmann House. He had been set up inside the house, but as the sun began to set behind the mountains, Shulman decided to move outdoors so that he might capture the dusk light. Neutra disagreed and insisted he stay indoors. With no time to lose, Shulman ignored Neutra’s demand and set up the camera on the lawn beside the pool. Facing west, the house began to glow as the sky darkened. In order to perfectly capture the moment, Shulman ran in and out of the house, switching various lamps on and off, opening and closing the camera shutter to let in just the right amount of light. At the last possible moment, he asked Mrs. Kaufmann to stretch out on the deck. The photograph, with its layers of light and dark tones, depicts the strong geometric forms of the house against a seemingly endless backdrop of mountain silhouettes. The composition, a work of art, has become one of Shulman’s two most reproduced photographs.

It was during the post war housing boom that Arts & Architecture magazine launched its Case Study housing program, hoping to promote modern housing of good quality and low cost. Of the two-dozen homes designed by such architects as Charles Eames, Craig Ellwood, A. Quincy Jones, Pierre Koenig, Neutra, and Soriano, Shulman took photographs of eighteen.

Shulman’s photographs were not without controversy. Some believed he made the structures he photographed look too beautiful. Critics of architectural photography chastised him for rearranging furniture to suit his perspective, or for bringing in props and posing models in the frame. Shulman was known for occasionally using filters or infrared film to make his photos look more dramatic and full of contrast. He would sometimes photograph from behind cut branches or plants from the nursery to hide the shadow of his camera, or to give the impression that a newly completed home was more fully landscaped. Shulman was always unapologetic about these tactics, citing his determination to not only take pictures, but to sell modernism.

Shulman conducted seminars in photography at USC, UCLA and other universities. In 1969, he was awarded the American Institute of Architecture’s Gold Medal for architectural photography, and has allowed the Los Angeles Conservancy to use his photographs for advocacy since its inception 30 years ago. In 2005, the Getty Center announced that it had acquired Shulman’s archive of 260,000 negatives, prints and transparencies. Shortly afterward, Woodbury University announced the opening of the Julius Shulman Institute which houses nearly 70,000 slides from Shulman’s own collection, including images of nature and personal travel photos.

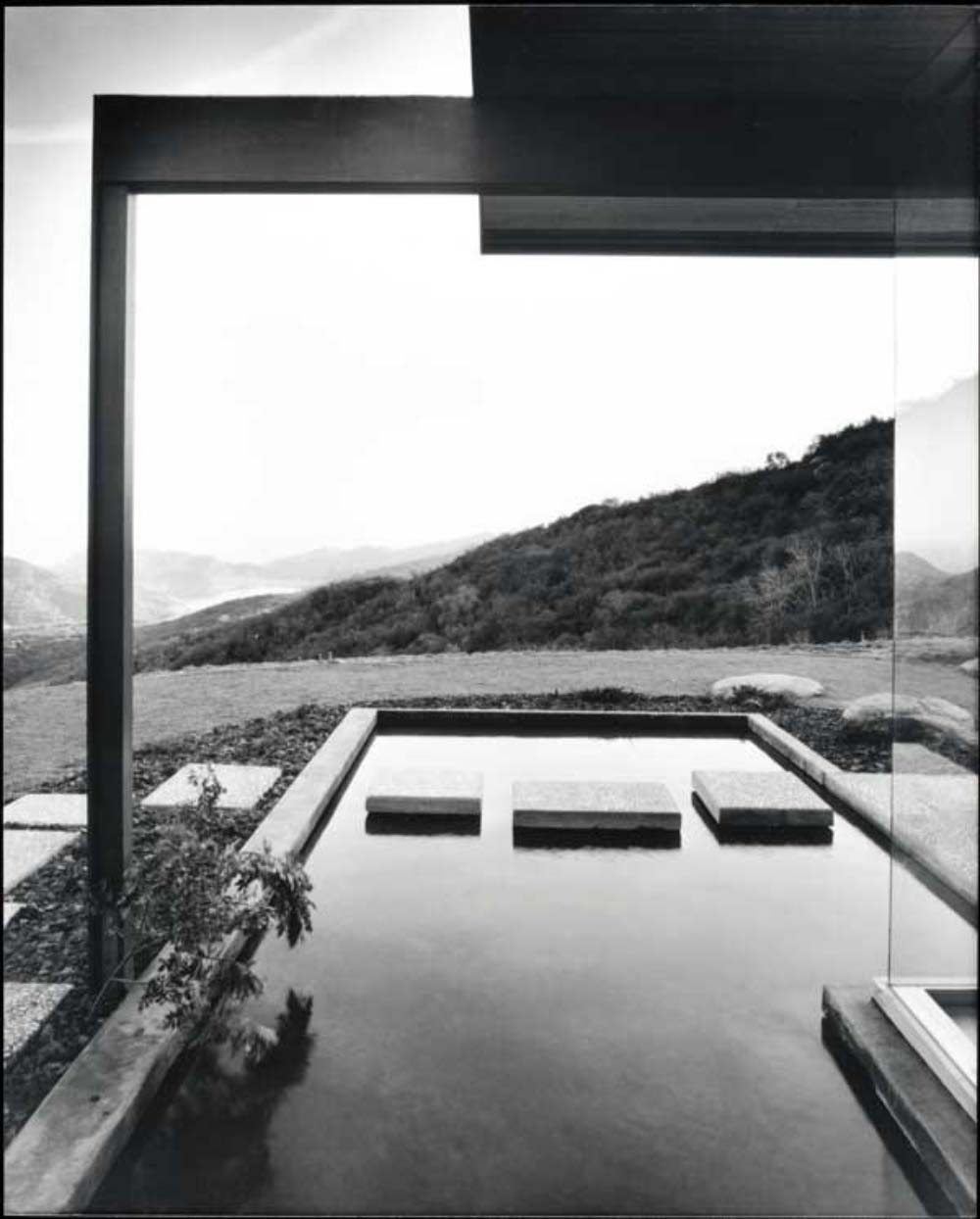

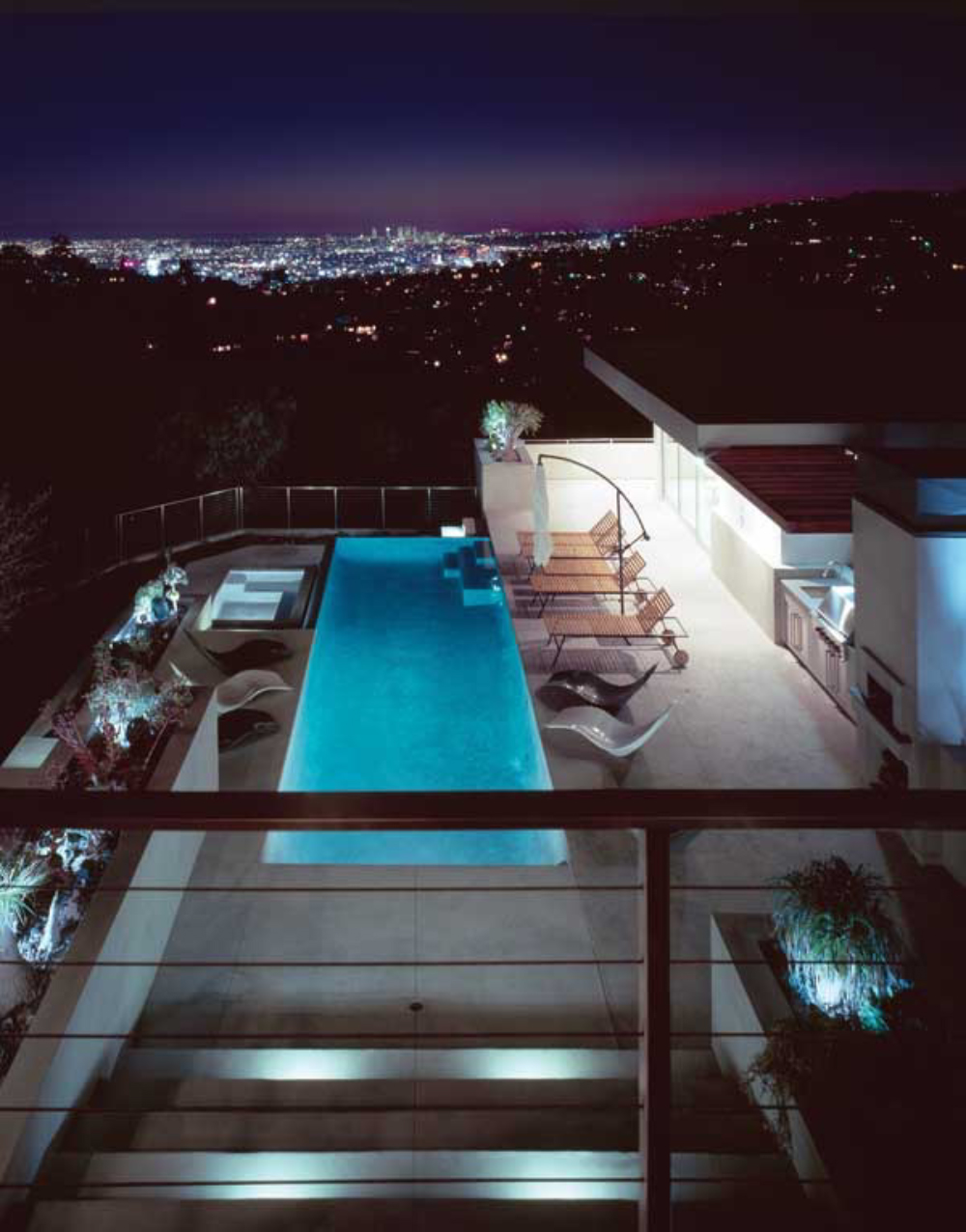

From 1999 until his death in July 2009, Shulman had been collaborating with German photographer Juergen Nogai. Together they had worked over 125 assignments from the Disney Concert Hall to the newly renovated Griffith Observatory. Their most recent work is currently being exhibited at the Craig Krull Gallery at Bergamot Station in Santa Monica, and the expanded collection will go on tour in Europe beginning spring 2010, the year which would have marked Shulman’s 100th birthday.

That Saturday afternoon last November, and the following months working with Julius and Juergen to photograph our recently completed Wild Oak Residence in Los Feliz, needless to say, has and will continue to have a profound impact on me. The memory, not unlike those formed in childhood, seems at one moment a haze, brief and fleeting, but at the same time perfectly preserved, with every detail clearly in focus. One of those memories we call upon in order to define who we are as human beings. A memory that serves to reveal our innermost thoughts, defines our character, and calibrates our moral strength. The experience was life changing for a young architect…well beyond the obvious, strangely indescribable…

Photos by Julius Shulman,

Photos of Wild Oak Drive by Julius Shulman and Juergen Nogai Photo of Julius Shulman and James Meyer by Michael Locke